It might sound like “blaming the victim,” but The Epoch Times has an interesting piece this week about the lack of funds for sustainable development, and the idea that some of the potential beneficiaries of the program are complicit in the situation. The IMF has its own plan for funding green projects.

Tag Archives: Copenhagen

Even with ‘Copenhagen,’ toasty times ahead

Last week I wrote about the post-COP15 emissions target deadline that whizzed by for most of the planet, and tried to put it into context. Of course, the larger question of what the resulting cuts would mean with regards to future warming remained unanswered, due to it being written during the wee hours of the morning. Fortunately, someone else also crunched the numbers and compared them to model predictions, New Scientist reports, arriving at a most unfortunate (but unsurprising) answer.

55 countries down…?

There’s a lot of press today about the fact that 55 countries have submitted emissions reduction pledges to the U.N. as the deadline drew passed; note that 27 of them are in the EU. New Scientist has a nice summary, and Reuters India lists most of the targets.

There’s a lot of press today about the fact that 55 countries have submitted emissions reduction pledges to the U.N. as the deadline drew passed; note that 27 of them are in the EU. New Scientist has a nice summary, and Reuters India lists most of the targets.

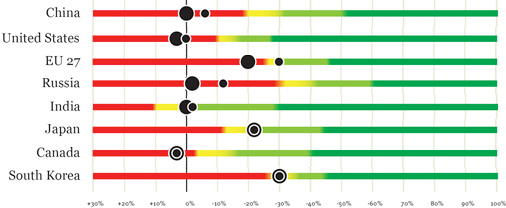

Some of the more disappointing targets include our own, our neighbors to the north, and Korea. “The US previously pledged a cut of 17% from 2005 levels by 2020 (equivalent to 3% from the conventional baseline of 1990)” (BBC). True to its word, the increasingly conservative Canadian government submitted the same relative target as the U.S. South Korea—whose emissions have more than doubled since 1990—has committed to an even smaller cut of 4% of 2005 levels. However, it has tries to play up the significance of these cuts by calling them a 30% cut from business as usual.

Below you can find a summary of the pledges of the top eight emitters (78%) of carbon dioxide, and what their effect might be. Please note that barring an international agreement in Mexico next winter, China and India’s targets are even less firm than those of other nations since they have vowed to decrease intensity (increase efficiency) by 40-45% & 16-20% respectively, rather than make cuts towards a specific target. These estimates are therefore a best case scenario under the unlikely condition of zero future growth.

| Baseline | 2007 | % Global | Cut | 2020 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MT CO2 | Year | MT CO2 | MT CO2 | ||||

| 1 | China | 6083.0 | 2007 | 6083.0 | 27.57% | 40.00% | 3649.8 |

| 2 | U.S. | 5857.1 | 2005 | 5853.5 | 26.53% | 17.00% | 4861.4 |

| E.U. | 4135.4 | 1990 | 3971.1 | 18.00% | 20.00% | 3308.3 | |

| 3 | Russia | 2302.6 | 1990 | 1579.0 | 7.16% | 20.00% | 1842.1 |

| 4 | India | 1369.9 | 2007 | 1369.9 | 6.21% | 16.00% | 1150.7 |

| 5 | Japan | 1069.4 | 1990 | 1235.1 | 5.60% | 25.00% | 802.1 |

| 8 | Canada | 543.4 | 2005 | 540.8 | 2.45% | 17.00% | 451.0 |

| 9 | South Korea | 361.4 | 2005 | 499.0 | 2.26% | 4.00% | 346.9 |

| World | 2007 | 29320.0 | 16.09% | 24600.9 | |||

MT = megatonne. approximately 2.2 billion pounds.

Countries 7 & 8 are the United Kingdom and Germany, both members of the European Union.

Sources: Emissions data, and pledges from stories linked in this post.

No Meaningful Agreement in Copenhagan. No Surprise.

Let’s see if we can grasp the so-called agreement reached in Copenhagan.

- Many of the Developed Countries (the North) have promised to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions as much as they (comfortably) can in the future. These are not binding commitments; just promises to make a best effort. And, they are all over the place in terms of the cuts they represent compared to past and present CO2 emission levels. A number of Developing Countries (the South, including China) have now promised to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. Again, nothing binding and wildly inconsistent targets and timetables. And, even if you add up all the promises, you won’t come close to getting the world on track to stabilizing greenhouse gas emissions at a (350–450 ppm) level by 2050 sufficient to forestall the worst effects of climate change over the rest of the century and beyond.

- The North has promised to come up with $30 billion over the next three years to help the South “fight” climate change. It’s not clear, though, how this money will be used or where it will come from. Presumably, some of it will be used to reduce CO2 emissions (although it is not clear what the best way to do that is or how such efforts should be prioritized). Some of it will have to be used to help countries adapt to sea level rise, increased storm intensity, periods of drought, adverse effects on biodiversity, and other disasters. (Which forms of adaptation should be pursued, are not clear.) Also, it is not obvious how this money will be administered or who will get it (presumably a disproportionate share should go to the poorest countries in Africa). The North says it will try to raise $100 billion by 2020, but, again, it is not clear where the money will come from, how it will be administered, or who will get it. Finally, these are just informal promises, not binding commitments.

- There was almost a new forest agreement, but at the end it got dropped. In Kyoto, the question of how to define and protect “sinks” (i.e., forests and oceans that absorb CO2) was not addressed. In Copenhagan, the leaders agreed that halting deforestation is “crucial.” Funds to pay countries, like Brazil, to conserve their forests are now supposed to be forthcoming. Note that rich nations like this idea because they want to count the funds they donate for this purpose toward “carbon credits” (thereby reducing the CO2 reductions they have to make in their own countries). It is not yet clear, though, how this system of carbon credits and forest preservation would work.

- As with all global treaty negotiations, there was a lot of uneasiness when the topic of monitoring and enforcement came up. No country can really force another to do what it doesn’t want to do—even if it has signed a treaty. Countries are sovereign. Most global agreements require countries to report regularly. But, in this case, if the reports don’t seem accurate, all the Climate Change Secretariat can do is ask for more information or clarification. It can’t double-check the data that countries submit or take independent measurements of its own. The South agreed for the first time, however, to report domestic CO2 emissions on a regular basis. There was some language discussed regarding “provisions for international consultation and analysis.” That’s as close as we’ll get to verification. Some observers had hoped that a new global panel of experts might have access to all monitoring equipment, data and technical specialists in each country so that suspect reports could be verified, but that didn’t happen.

- The so-called “Statement on Temperature” agreed to in Copenhagen says that the nations agreed that any global increase in future temperature should be kept to under two degrees Celsius. Since the new agreements specifies no targets, timetables, enforcement mechanisms, provisions for technology sharing between the North and the South, or ways of enhancing capacity building, it’s hard to take such a statement seriously. Saying it should be done, but not saying how, is tantamount to saying nothing.

- None of the promises made in Copenhagen are binding. Maybe, in the next year or two, a formal Protocol will be drafted that explains how implementation of these various commitments is supposed to happen. Until then, though, we’ll be operating under the Rio Climate Change Convention and the Kyoto Protocol.

What happens when the Kyoto agreement runs out in 2012? It appears that we will have no binding targets in place to bring global greenhouse gas emissions to a level (450 ppm? by 2050) needed to forestall dangerous temperature increases. We certainly won’t have the level of cooperation between North and South required to tackle the climate change problem over the long haul. Many countries in the South resent the way they were (once again) left out of the last minute wheeling and dealing in Copenhagen. And, tossing money at them, no matter how many billions, without ever agreeing in principal that the North is responsible for the climate change mess we are currently in, just puts off the day we can achieve the global collaboration required to address the problem effectively. Small island nations face total destruction. The numbers of international refugees that will have to move from low-lying coastal areas devasted by meterological events is sure to increase markedly. Unfortunately, nothing will be done to jump-start Southern efforts to achieve more sustainable patterns of development. In short, after Copenhagen, the climate change problem will continue to get worse at an even faster clip.

What should have been done and what can still be done to turn this situation around? First, we need to alter the system of global treaty drafting. Each region of the world should bring together governmental and non-governmental interests on a specific multi-year timetable to produce a draft global treaty that takes account of its needs and sort out its responsibilities for achieving proportionate greenhouse gas mitigation efforts sufficient to reach the required 450 ppm goal by 2050. Two or three countries in each region should immediately mobilize such efforts. Using a common template—developed by the Climate Change Secretariat which still has a 160±country mandate—each regional caucus should spell out ten year incremental reduction targets sufficient to meet the 450 ppm goal by 2050, explicit strategies that countries can use to meet these targets if they have to, the cost implications of meeting such targets (netting out the costs of not meeting them as well), ways reasonable data reporting and verification responsibilities might be met, institutional capacity building requirements, financial forecasts likely to have an impact on implementation, and possible financial or in-kind contributions each country needs or could provide). This needs to be done in eight to ten regions of the world. Each regional “caucus” should draft its suggested version of a new global agreement to meet greenhouse gas reduction requirements responsibly and designate five members from its caucus to participate in a global treaty-making council with responsibility for reconciling the differences among the proposed regional drafts. The Global Congress would have to be mediated by an international panel of skilled facilitators acceptable to all the regions. A Congress of 40–50 regional representatives would need a year or more to prepare a meaningful treaty the takes account the differences among all the regional drafts. The final version of the treaty would then be sent to each national legislative body to ratify (not at another Copenhagan-style type fracus). When a minimum of 2/3 of the countries in each region ratifies it, and a minimum of 2/3 of the regions ratify it, it would come into force. If 2/3 of the countries in 2/3 of the regions ratified the treaty, those 130 countries would be in a position to take action (under a range of trade and other treaty regimes) to pressure any and all hold out countries to ratify the new Climate Change treaty. If a county won’t sign the new treaty, they ought not be eligible to participate in international trade regimes. If they don’t sign, they ought not be eligible for assistance from any multinational banks. Since all the same countries are part of all these regimes, the climate change treaty signers would have sufficient numbers (and through the process I am describing) sufficient legitimacy, to make this happen.

Let’s get to work.

Opening the talks

While we still have great expectations of the upcoming talks in Copenhagen are all fine and dandy, it’s a rather elite event about a topic that touches us all. There have been efforts to democratize the discussion, such as the Museum of Science’s, “World Views on Global Warming,” but participation is still limited to those who can be physically present. Of course, you have another chance to do so at a follow-up session tomorrow (12/5) morning. MIT’s Center for Collective Intelligence has also launched a new project, the Climate Collaboratorium, to allow people to share, vote on and discuss ideas about reducing emissions on a large scale.

While we still have great expectations of the upcoming talks in Copenhagen are all fine and dandy, it’s a rather elite event about a topic that touches us all. There have been efforts to democratize the discussion, such as the Museum of Science’s, “World Views on Global Warming,” but participation is still limited to those who can be physically present. Of course, you have another chance to do so at a follow-up session tomorrow (12/5) morning. MIT’s Center for Collective Intelligence has also launched a new project, the Climate Collaboratorium, to allow people to share, vote on and discuss ideas about reducing emissions on a large scale.

Frogs in a pot: Lessons from the BECC conference

Imagine if I offered someone a 17% return on their investment, that would help to prevent catastrophic long-term environmental consequences and improve the comfort and value of their home. Now envision this person shrugging off this offer and spending their money instead on upgrading their car to a fancy SUV that immediately devalues over time. Would you call this action “rational”?

Imagine if I offered someone a 17% return on their investment, that would help to prevent catastrophic long-term environmental consequences and improve the comfort and value of their home. Now envision this person shrugging off this offer and spending their money instead on upgrading their car to a fancy SUV that immediately devalues over time. Would you call this action “rational”?

This was the crux of the Behavioral, Efficiency, and Climate Change conference I attended this week, that looked into the psychological motivations of human beings, exploring why they continually make poor choices and uncover the motivating factors to help people make better decisions. Opening keynote speaker, Dan Ariely author of Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape Our Decisions, is a behavioral economist who explores such questions as, “Do you know why we still have a headache after taking a five-cent aspirin, but why that same headache vanishes when the aspirin costs 50 cents?

In one poignant example, he shared his experience as a bomb victim in an Israeli hospital for 4 months. When he had to get his bandages removed the nurses wanted to rip them off quickly rather than a slow undressing. He argued for the latter, but they said that quick removal was the less painful option. This brought him down the road of behavioral psychology and through his own experiments with volunteers, using interesting pain inducing techniques, he found that people preferred slow prolonged pain rather than intense shorter experiences. He brought his evidence back to the nurses who cared for him and upon learning about his findings one nurse exclaimed: What about my pain of having to experience your screams or the pain of adopting something new?

The four day conference explored many of the questions of why people make irrational decisions, all the while we think of ourselves as unbiased and objective. Take climate change, despite the evidence that our collective impacts are surpassing the worst case scenarios predicted by the IPCC, support for Climate Change action is on a decline. This can be primarily explained by humans being hard wired to deal with immediate threats. Here are a couple of other interesting reasons on why we do not shift our behaviors to fight climate change:

- Choices are habitual

- Lifestyle change requires immediate sacrifices: time, money, and doing things differently than peers

- People pursue risk seeking rather than risk avoidance activities

- People believe we can adapt and that technology will save us

- It is hard for us to understand or worry about intangible future consequences and we are always looking for an enemy– it is hard to believe it is us!

- Wide range of measures make it difficult for people to adopt– Where do I start?

While many believe that the invisible hand of the market will save us, time and again this assertion has been proved wrong such as the recent collapse of ocean fisheries. Just last week, fishing nations agreed to a 30% decline in fishing yields, giving blue fin tuna a 60% chance of recovering in 15 years– tuna’s numbers have been decimated to 15% of their historical size.

Ultimately, some of the biggest findings from leading social scientists, economists, and industry experts revealed that humans are typically not moved by facts but by emotions. Our deeply held beliefs prevent us from integrating new, sometimes life saving information. I leave you with some exciting information provided by Hannah Choi Granade, lead author of the McKinsey report on “Unlocking Energy Efficiency in the U.S. Economy“. If our nation were to invest $520 billion dollars in upfront investments, we would capture $1.2 trillion dollars in energy savings– and that is without behavior changes. That would lead to a 23% decline in projected demand, saving enough electricity to power Russia and provide natural gas to Canada for a year.

Let’s hope our leadership comes through for Copenhagen and beyond!

Global Climate Chicken

Congress will have a lot on its plate when it returns to session in approximately two weeks: health care, war/torture, food safety and of course climate change. Indeed, it’s beginning to look like, once again, the hopes of significant international effort to redress global warming are—arguably with good reason—landing square on the shoulders of Uncle Sam. As reported in many places yesterday, the Indian government has all but asked to be shamed into participating, and for developed nations to “call it’s bluff.” In a similar vein, and also making the rounds on Wednesday, was a statement from the Swedish minister of environment suggesting that: If the U.S. leads, China will follow. Alas, the fate of Waxman-Markley is still unclear, but at least this time Congress seems to be working towards the goal before international negotiations begin rather than against it. Perhaps you’d like to give your elected officials an encouraging nudge?

Youth take the lead on climate change and planet stewardship

Today was a sad day for the environment, with reports released on the safety of our rivers and oceans being at stake. It is hard to imagine that every river in the US has fish contaminated with mercury or that the plastic bags circulating in the Pacific Ocean in an area twice the size of Texas is now being found to be breaking down into a toxic soup of bisphenol-a. More than ever, we need a movement to rise up and protect this fragile blue orb that supports life as we know it.

Today was a sad day for the environment, with reports released on the safety of our rivers and oceans being at stake. It is hard to imagine that every river in the US has fish contaminated with mercury or that the plastic bags circulating in the Pacific Ocean in an area twice the size of Texas is now being found to be breaking down into a toxic soup of bisphenol-a. More than ever, we need a movement to rise up and protect this fragile blue orb that supports life as we know it.

What gives me hope, is an article I came across today, that the seeding of such a movement is underway. Over seven hundred youth from across the globe have gathered in Daejeon, Republic of Korea, to call on leaders to address Climate Change at Copenhagen in December and involve youth in environmental decisions. Young people comprise of 3 billion of the global population and will be faced by the growing environmental challenges plaguing the planet. They asked that environmental education be included in their curriculum and that global citizens take real steps to reduce their impacts on the planet like using public transportation and purchasing environmentally friendly products.

One of the most poignant statements from a youth delegate from the Netherlands, “We are the generation of tomorrow. The decisions that are made today will define our future and the world we have to live in. So we young people of the world urge governments to commit to a strong post-Kyoto climate regime. It is our lives we are talking about.” Will the public and political leadership heed their call?

Climate Bill Passes the House

The controversial climate bill passed through the House on Friday and pressure is mounting for the leadership in the Senate to take up the bill. Republicans see the climate bill as too costly for for households and view the bill’s carbon reduction mandates as having a harmful effect on industry. Some environmentalists are also not in support of the house bill, raising concerns over the reduction targets being too low and giving carbon allowances away to industrial polluters.

The controversial climate bill passed through the House on Friday and pressure is mounting for the leadership in the Senate to take up the bill. Republicans see the climate bill as too costly for for households and view the bill’s carbon reduction mandates as having a harmful effect on industry. Some environmentalists are also not in support of the house bill, raising concerns over the reduction targets being too low and giving carbon allowances away to industrial polluters.

It is likely the Senate will vote on a version of the bill by fall, which would then need to be hashed out between the two houses. The climate legislation is a contentious bill for republicans and industry with many legislators calling global warming an outright hoax. Paul Krugman published an article “Betraying the Planet,” in the New York Times on how majority of the climate bill no votes were from global warming denialists.

In addition, even though the American public wants to see action on climate change, there is growing concern about cap and trade and the potential cost impacts that will have on their wallets. Independent research groups have estimated the climate bill will cost taxpayers approximately $175 per year, while industry is estimating much higher costs to American citizens.

The United States is also facing international pressure to have a strong climate policy in place for the United Nations Climate Conference in Copenhagen in December to develop a new Kyoto protocol. It is likely that a national climate bill will be passed by the end of the year, but it is unclear whether the US’ national climate bill will lead the way or serve as an ineffective panacea to our growing climate crisis.