It’s a huge success. It hasn’t gone anywhere. Actually, it’s a little of both.

It’s a huge success. It hasn’t gone anywhere. Actually, it’s a little of both.

Fifty states and six territories have launched “Cash for Appliances” programs since late last year. Each one had the same amount of money – about a dollar per resident – but the results have been wildly different. Some states ran through their entire rebate budgets in hours; others can’t seem to give away their money. What’s been going on?

Cash for Appliances, modeled on (or at least nicknamed after) last year’s “Cash for Clunkers” program, was funded as part of the $787 billion stimulus bill. Unlike “Cash for Clunkers”, the appliance rebate program wasn’t designed and administered by the federal government. Instead, the government directed $300 million to the 50 states (plus DC and several American territories), at a ratio of roughly $1 per person in each state. Each state then had the opportunity to design their own program within the general guidelines given by the government.

As you’d imagine with a lot of cooks in the kitchen, no two states designed their rebate program in the exact same way: rebate amounts, categories, eligibility, application processes and marketing plans have all differed. As have the results… Ten states had crushing consumer demand that caused them to run out of rebate funds within 4 days of the respective program start dates, with complaints of flooded call centers and crashing websites. Thirteen other states still have desperate operators standing by and literally can’t give away their money.

Comparing State by State Rebate Programs

It’s not just a matter of some states having better deals than others. Take, for example, refrigerator rebates in Massachusetts, Minnesota and California. The programs in all three states offered $200 rebates on efficient refrigerators. Massachusetts and Minnesota “sold out” in 1 day and 2 days respectively. California? Same rebate amount, but the program has been open since April and still has $19 million in rebates unredeemed.

Across the country, the rebate categories and amounts are all over the board:

| Category | Smallest State Rebate | Largest State Rebate |

| Refrigerators | $50 | $700 |

| Clothes Washers | $35 | $800 |

| Freezers | $25 | $600 |

| Dishwashers | $25 | $400 |

| Air Conditioners | $20 | $1,075 |

| Furnaces | $100 | $2,000 |

| Heat Pumps | $75 | $2,000 |

| Water Heaters | $100 | $1,400 |

| Solar Water Heaters | $150 | $1,200 |

| Boilers | $100 | $1,200 |

So what attributes matter the most when it comes to determining whether a state program sells out quickly or not at all? The answers aren’t as straightforward as you’d think. We did some analysis to compare each of the programs to see what predicted their likelihood to sell out.

What Doesn’t Matter

Average Electricity Rates: One of the biggest surprises in analyzing the state by state rebate data is that the average price of electricity in a state has almost no impact on how popular its Cash for Appliances program is. Consumers don’t seem to be thinking about this program in terms of its ability to save them money over the long-term – otherwise, we’d expect to see that the states with much more expensive electricity selling out their rebate programs much more quickly than those that have relatively cheap power.

Non-Appliance Rebates: There are the “shiny” appliances (refrigerators, washers, freezers and dishwashers), and then there are the “boring” systems (air conditioners, furnaces, heat pumps, water heaters, boilers and solar water heaters). There’s almost no correlation between the number of “boring” categories that a state has rebates for, or the maximum amount of any of those rebates, and the speed at which the state has gone or is going through their Cash for Appliances budget. While we haven’t seen break-downs for many states in terms of the numbers of each type of rebate that have been redeemed, this result indicates that most people aren’t being motivated by the number or dollar figures of non-appliance rebates.

What Matters a Little Bit

Number of “Shiny” Appliance Rebate Categories: There are four basic appliance categories where states can offer rebates (refrigerators, freezers, dishwashers and clothes washers). Generally speaking, the states that offer rebates in 3 or 4 of those categories are more likely to have run through their rebate dollars quickly than those that have offered rebates in fewer appliance categories.

The fact that states that offer smaller rebates on a broader set of appliances have handed out their money faster than states that offer larger rebates on fewer types of appliances may mean that rebates aren’t successfully channeling consumers into buying specific appliances, but rather “catching” buyers who were already planning purchases.

In Pennsylvania, for instance, there are no rebates on “basic appliances”. All the rebates being offered in that state are for the behind-the-scenes systems for heating water and air (furnaces, boilers and water heaters) –systems in the home that utilize far more energy than kitchen and laundry appliances. And yet, Pennsylvania is one of the “slowest” states utilizing their Cash for Appliances money: of their $11.9 million, they’ve only given out $2 million as of early July. Does that mean that Pennsylvania is failing in their “Cash for Appliances” program? As an economic stimulus, it has clearly not injected as much activity as other “fast” states. But in the longer term, its rebate program should save Pennsylvanians more money than states using their money on appliance rebates only – saving more kWh per rebate dollar spent – if homeowners would just use the program!

Highest “Shiny” Appliance Rebate Dollar Amount: If you exclude several outlying state programs, where very large appliance rebates are provided but only to low-income (Kansas, Oregon) and disabled (Alaska) residents, there’s some correlation between the dollar amount of the largest appliance rebate and how quickly the program dollars ran out, though not nearly as much as whether a program required reservations.

What Really Matters

“Do you have reservations, sir?”: The number one predictor of whether a state rebate program sold out quickly didn’t have anything to do with how generous the rebates were. It actually turned out to hinge on the program’s design. Virtually all the “fast” states required consumers to pre-reserve a rebate application before making a purchase. These states set up websites and call centers that “opened” at a certain date and time, creating an “event” that turned into a feeding frenzy of activity, before closing down within days, or even hours.

Think of the lines around the block at your local Apple store each time a new version of the iPhone comes out. With the iPhone 4, everyone was just standing in line for a reservation! Do you really think Apple’s product marketers could have been taken by surprise by consumer five times in a row (4 iPhone versions and the iPad)?

Ten of the 17 “fastest” states required consumers to reserve a rebate before purchasing a qualifying appliance. Six others had hybrid programs where consumers could either reserve ahead of time or get the discount at the point of sale (if available). Of the 15 “slowest” states, 11 have no reservation system, and three others have optional reservation systems. Basically, all the “slow” states use mail-in rebates after purchase.

Conclusions

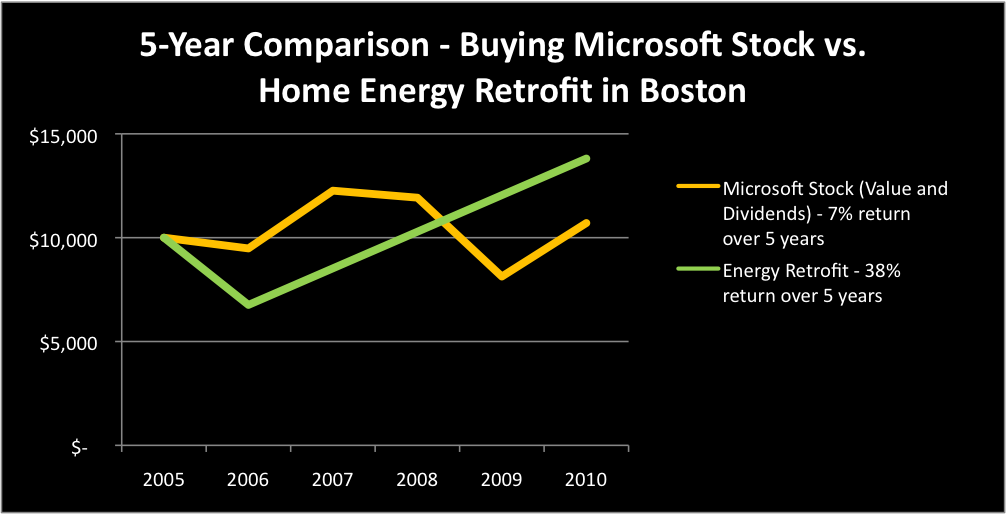

For consumers, there’s not much more to say than to give the advice to make calculated, rational decisions about the upfront cost of energy efficiency measures, the available rebates and the 3-5 year payoff. Of course, it’s been pretty well documented in recent behavioral economics research that most consumers don’t behave rationally. So, how about this? At least make sure that you’re aware of all the state, utility and federal energy rebates and tax credits that you can “stack” together and pay for your projects. And, if you’re not sure which projects are the best investment, EnergySavvy has an online energy analysis tool to help you figure it out.

For rebate program designers in government, utilities or manufacturers, there are a few lessons that can be taken away from the Cash for Appliances results:

- Create demand through scarcity by requiring pre-reservation for new rebate programs. For rebate programs like Indiana and Pennsylvania (and like many utility rebate programs across the country), that only pay out non-appliance rebates, a potentially effective strategy to kick-start demand would be to re-launch the program with higher rebates for the same back-end measures, but require consumers to pre-reserve their rebate on a specific launch date.

- Bundle “shiny stuff” (basic appliances) and “boring stuff” (HVAC systems) together to increase the uptake of less exciting, but greater energy saving, systems.

- Catch the “already upgrading” crowd by offering rebates on a wide set of categories but only on the most efficient models in each category. The program may not be stimulating purchases that wouldn’t have happened already, but it can nudge consumers to the highest efficiency products in each category.

The data from the Cash for Appliances program results fit with academic research on consumer behavior.

“The variable rates of uptake based on seemingly trivial factors such as creating a sense of urgency are further evidence that, when the goal is to encourage consumers to act in their best interest, giving them some reason other than pure rationality can be surprisingly effective,” said Michael I. Norton, Associate Professor of Marketing at Harvard Business School, “Inserting some excitement into behaving well – in some sense, copying the way parents induce their children to eat their vegetables via airplane noises – should always be an important consideration for policymakers interested in encouraging behavior change.”

For more information on this report and analysis, contact Scott Case at EnergySavvy.com.

On

On

China exceeded U.S. investment in clean energy for the first time last year with deployments totaling $34.6 billion. The country still has a long way to go to clean up it’s emissions—China surpassed the US as the global leader in C02 emissions several years ago—but they’re moving quickly to clean up their act.

China exceeded U.S. investment in clean energy for the first time last year with deployments totaling $34.6 billion. The country still has a long way to go to clean up it’s emissions—China surpassed the US as the global leader in C02 emissions several years ago—but they’re moving quickly to clean up their act.

It is time again for the city of Cambridge’s Go Green Awards, which recognizes businesses and organizations that take exceptional environmental actions in at least one of five areas—energy use, transportation, waste reduction, stormwater, and climate protection. Self nominations are accepted.

It is time again for the city of Cambridge’s Go Green Awards, which recognizes businesses and organizations that take exceptional environmental actions in at least one of five areas—energy use, transportation, waste reduction, stormwater, and climate protection. Self nominations are accepted. On Sunday, February 21, eighteen volunteers participated in a community canvass campaign to spread awareness about simple home improvements to save money, energy, and the planet. The event organized by the

On Sunday, February 21, eighteen volunteers participated in a community canvass campaign to spread awareness about simple home improvements to save money, energy, and the planet. The event organized by the